Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Why do we tell stories?

Distinguished Professor Brian Boyd (University of Auckland) on stories and storytelling:

Monday, 28 September 2015

Friday, 25 September 2015

Looking back: 2014 York Mystery Play Production

This was a wagon production, with the plays performed on pageant wagons wheeled from place to place along a fixed route. When each wagon stopped at the so-called 'stations,' its play was performed.

The production was pruned down somewhat from what it would have looked like in the Middle Ages - twelve plays were performed at four stations. The original play cycle had forty-eight pageants (or plays) at twelve stations. (Somehow, all forty-eight plays were squeezed into one day, beginning at dawn and ending around midnight.)

Nevertheless, the production gave a good sense of the demands and practicalities of wagon playing (you can read more about this here, although it is from a largely modern perspective instead of a medieval one!)

And there is more background information on the production here.

Much scholarly ink has been expended in wondering whether the medieval wagons were positioned end-on or broadside, and whether they were placed on the left or right side of the street. The latter question is, like many issues surrounding the plays, one that can be argued either way and probably never settled conclusively. But regarding the first question, it seems most likely that the guilds adapted the wagons to whatever best suited the demands of their particular play.

Plays that required a lot of scenery were probably played broadside, allowing the backdrop to be positioned at the back edge of the wagon, on display to the audience:

Those that had little or no scenery could be played end-on, using the wagon as a thrust stage into the audience. This video is of the Crucifixion (played end-on). It shows how the cross was raised from the wagon floor into the upright position, using ropes and the tow-bar of the wagon as a hinge:

The York Crucifixion play omits the two thieves and after looking at the video it is easy to see why; three crosses could never have fitted onto one wagon and the process of raising even one cross is complicated and somewhat dangerous! Having three crosses would only have trebled the difficulty and the risk.

The production was pruned down somewhat from what it would have looked like in the Middle Ages - twelve plays were performed at four stations. The original play cycle had forty-eight pageants (or plays) at twelve stations. (Somehow, all forty-eight plays were squeezed into one day, beginning at dawn and ending around midnight.)

Nevertheless, the production gave a good sense of the demands and practicalities of wagon playing (you can read more about this here, although it is from a largely modern perspective instead of a medieval one!)

And there is more background information on the production here.

Much scholarly ink has been expended in wondering whether the medieval wagons were positioned end-on or broadside, and whether they were placed on the left or right side of the street. The latter question is, like many issues surrounding the plays, one that can be argued either way and probably never settled conclusively. But regarding the first question, it seems most likely that the guilds adapted the wagons to whatever best suited the demands of their particular play.

Plays that required a lot of scenery were probably played broadside, allowing the backdrop to be positioned at the back edge of the wagon, on display to the audience:

| http://yorkmysteryplays.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/agony-in-the-garden-2010.jpg |

(This photo, showing the Agony in the Garden, is actually from the 2010 production.)

Those that had little or no scenery could be played end-on, using the wagon as a thrust stage into the audience. This video is of the Crucifixion (played end-on). It shows how the cross was raised from the wagon floor into the upright position, using ropes and the tow-bar of the wagon as a hinge:

The York Crucifixion play omits the two thieves and after looking at the video it is easy to see why; three crosses could never have fitted onto one wagon and the process of raising even one cross is complicated and somewhat dangerous! Having three crosses would only have trebled the difficulty and the risk.

Thursday, 24 September 2015

Harry trumps Hamlet

According to The Telegraph, anyway: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/theatre/what-to-see/henry-v-royal-shakespeare-company-review/

✭✭✭✭✭

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead.

In peace there's nothing so becomes a man

As modes stillness and humility:

But when the blast of war blows in our ears,

Then imitate the action of the tiger;

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood,

Disguise fair nature with hard-favour'd rage

[...]

... On, on, you noblest English,

Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof!

[...]

... And you, good yeoman,

Whose limbs were made in England, show us here

The mettle of your pasture; let us swear

That you are worth your breeding; which I doubt not;

For there is none of you so mean and base,

That hath not noble lustre in your eyse.

I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start. The game's afoot:

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge

Cry 'God for Harry, England and Saint George!'

Dido and Aeneas

The Handel Consort and Quire (phew, what a mouthful) is performing Purcell's Dido and Aeneas Saturday 3rd & Sunday 4th October.

Saturday 7:30pm, Pitt St Methodist Church, CBD

Sunday 5pm, St Andrew's Church, Pukekohe

Door prices: Adult $40 Seniors $35 Students FREE!!!! (must have ID)

Book here (scroll down to the bottom of the page to book through Eventfinder) and get $10 off the door prices.

Anyone who's thinking of going on the Saturday, let me know :D

Wednesday, 23 September 2015

Unpacking Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Great wonder grew in hall

At his hue most strange to see,

For man and gear and all

At his hue most strange to see,

For man and gear and all

Were green as green could be.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (or SGGK as students of the poem abbreviate it) is one of my favourite poems. I love the force, rhythm and richness of the language, the vivid descriptions, and the characters - the mysterious, magical Green Knight and, well, who couldn't like Sir Gawain?

The poem is from the late fourteenth century, written in the dialect of the West Midlands. The author of the poem is, like many medieval authors, unknown. Whoever it was is usually identified as the 'Pearl Poet' because the poem Pearl is thought to have been written by the same person.

Because the poem contains long and quite detailed descriptions of the natural landscape, scholars have tried to map the poem onto the Midland countryside, trying to identify the exact locations described in the poem. This is a fairly hopeless undertaking and every scholar will have their own pet theory. Generally speaking, the poem is set somewhere in the Cheshire/Staffordshire/Derbyshire region, though Gawain's quest also takes him down into North Wales.

The poem is written in the alliterative style, which means that within each line there are at least three, sometimes more, words beginning with the same initial letter:

Ye may be seker bi this braunch that I bere here

That I passe as in pes, and no plycht seche.

Pearl manages to achieve the very difficult task of making the lines both alliterative and rhyming. Sir Gawain's rhyme scheme is much looser, almost to the point of being non-existant. This makes the verse flow much more freely. With alliteration and rhyme, the verse becomes quite stilted. Sir Gawain's verse flows more melodically and litingly than Pearl's.

The poem is divided into four 'fyttes' (usually modernised to 'fitt'), or parts. Within each fitt the verse is further broken up by bob-and-wheel structures. These bring each stanza to a conclusion - the bob-and-wheel is the poetical equivalent of tying the stanza up with a neat bow.

The bob-and-wheel is a set of five lines much shorter than the preceeding lines of the stanza. The bob is a very short line that seems to 'hang' off the rest of the stanza. The wheel is alliterative but also rhymes with the bob:

Such a fole upon folde, ne freke that hym rydes,

Was never sene in that sale wyth syght er that tyme, (last couplet of stanza)

with yye. (bob)

He loked as layt so lyght (wheel)

So sayed al that hym syye;

Hit semed as no mon mught

Under his dynttes dryye.

As far as readability goes, the Middle English of Sir Gawain is reasonably heavy going, although using a well-glossed edition makes it much easier (I have an old 1970 Everyman edition). But there are several translations of the poem available - two of the best are Marie Borroff's and Simon Armitage's. I used the Norton Critical edition of Marie Borroff's version when I was working on the poem last year.

Simon Armitage has also done a very good documentary on the poem:

There is a further host of info on the poem over at the Luminarium website: http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/gawain.htm

And the story of the poem? That is something you will have to find out for yourselves!

Opening quote from Marie Borroff, ed. and trans., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (New York, London: W.W. Norton, 2010), l.147-50.

Middle English quotes from Pearl, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, edited by A.C. Cawley (London: Everyman, 1970).

Monday, 21 September 2015

Sea Fever

I must down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel's kick and the wind's song and the white sails shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea's face and a grey dawn breaking.

I must down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull's way and the whale's way where the wind's like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick's over.

John Maesfield, "Sea Fever" [1902], in Penguin's Poems By Heart: Poetry to Remember and Love For Ever, edited by Laura Barber (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 27.

| http://4vector.com/i/free-vector-sailing-ship-clip-art_108452_Sailing_Ship_clip_art_hight.png |

Friday, 18 September 2015

English: a very rough guide

When people ask what my thesis is in and I say 'Middle English,' there are two types of response (discounting the blank stare which is far and away the most common):

1. "Oh... Shakespeare!"

2. "Oh... really old English!"

Not quite. Middle English is neither Shakespearean English nor Old English. Middle English is... well, somewhere in the middle!

This is my own rough guide to the development of English over the last thousand years or so. The period boundaries are fluid - Old English did not become Middle English overnight, for example - and within each period there will be a lot of variation as well. Thirteenth century Middle English is quite different from that of the fifteenth century. Before the invention of the printing press (around 1440), which started the process of standardisation in spelling and vocabulary, there were also huge dialectal variations (northern, southern, midland, and Anglian are the main ones) within the language. The first recorded instance of a southerner making fun of the northern English accent is in Chaucer's Reeve's Tale.

Old English (OE): pre-Norman conquest (1066). To someone unused to it, impossible to read.

Hwæt! We Gar-Dena in gear-dagum

þeod-cyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon!

First three lines of Beowulf. Translated into modern English, they read:

What were we War-Danes in our yore-days?

Tribal-Kings! Truly cast that glory past,

how the counts had courage vast!

Via http://www.csun.edu/~ceh24682/beowulf.html

Middle English (ME): from the Conquest to the end of the Plantagenets (Richard III, died 1485, was the last Plantagenet king). Once you work out that þ (thorn) = th, v = u and ȝ (yogh) = y it is surprisingly easy to read, especially if you use editions in modern spelling.

Al men þat walkis by waye or strete,

Take tente ȝe schalle no trauayle tyne.

Byholdes myn heede, myn handis, and my fete,

And fully feele nowe, or ȝe fyne,

Yf any mournyng may be meete,

Or myscheue mesured vnto myne.

Crucifixio Christi l.253-8, in The York Plays, edited by Richard Beadle (Oxford: Early English Text Society for Oxford University Press, 2009).

All men that walk by way or street,

Take tent ye shall no travail tine.

Behold mine head, mine hands, and my feet,

And fully feel now, ere ye fine,

If any mourning may be meet,

Or mischief measured unto mine.

Crucifixion l.253-8, in York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling, edited by Richard Beadle and Pamela King (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009).

All you men who walk by in the street,

Take heed and notice My suffering!

Behold My head, My hands, and My feet,

And consider well, before you pass on,

If any sorrow can match,

Or any misfortune compare to Mine.

The first passage (part of Christ's speech from the cross in the York Crucifixion play) is Middle English in its original spelling, the second is Middle English but in modern spelling, and the third is 'translated' into modern English.

Early Modern English (EME): from the Tudors (Henry VII was the first Tudor king) to the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, thus encompassing the entire Tudor period, the Elizabethans, Jacobeans, and the period of the Civil War. This is the language of Shakespeare.

If music be the food of love, play on;

Give me excess of it, that surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken and so die.

That strain again, it had a dying fall;

O it came o'er my ear like the sweet sound

That breathes upon a bank of violets,

Stealing and giving odour.

William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night I.I.1-7, edited by Rex Gibson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Modern English (sometimes New English or NE): from the mid-seventeenth century onwards.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice [1813], edited by Vivien Jones (London: Penguin Books, 1996), 5.

Present Day English (PDE) is, like, what we speak now, innit? c u l8r!

1. "Oh... Shakespeare!"

2. "Oh... really old English!"

Not quite. Middle English is neither Shakespearean English nor Old English. Middle English is... well, somewhere in the middle!

This is my own rough guide to the development of English over the last thousand years or so. The period boundaries are fluid - Old English did not become Middle English overnight, for example - and within each period there will be a lot of variation as well. Thirteenth century Middle English is quite different from that of the fifteenth century. Before the invention of the printing press (around 1440), which started the process of standardisation in spelling and vocabulary, there were also huge dialectal variations (northern, southern, midland, and Anglian are the main ones) within the language. The first recorded instance of a southerner making fun of the northern English accent is in Chaucer's Reeve's Tale.

Old English (OE): pre-Norman conquest (1066). To someone unused to it, impossible to read.

Hwæt! We Gar-Dena in gear-dagum

þeod-cyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon!

First three lines of Beowulf. Translated into modern English, they read:

What were we War-Danes in our yore-days?

Tribal-Kings! Truly cast that glory past,

how the counts had courage vast!

Via http://www.csun.edu/~ceh24682/beowulf.html

Middle English (ME): from the Conquest to the end of the Plantagenets (Richard III, died 1485, was the last Plantagenet king). Once you work out that þ (thorn) = th, v = u and ȝ (yogh) = y it is surprisingly easy to read, especially if you use editions in modern spelling.

Al men þat walkis by waye or strete,

Take tente ȝe schalle no trauayle tyne.

Byholdes myn heede, myn handis, and my fete,

And fully feele nowe, or ȝe fyne,

Yf any mournyng may be meete,

Or myscheue mesured vnto myne.

Crucifixio Christi l.253-8, in The York Plays, edited by Richard Beadle (Oxford: Early English Text Society for Oxford University Press, 2009).

All men that walk by way or street,

Take tent ye shall no travail tine.

Behold mine head, mine hands, and my feet,

And fully feel now, ere ye fine,

If any mourning may be meet,

Or mischief measured unto mine.

Crucifixion l.253-8, in York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling, edited by Richard Beadle and Pamela King (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009).

All you men who walk by in the street,

Take heed and notice My suffering!

Behold My head, My hands, and My feet,

And consider well, before you pass on,

If any sorrow can match,

Or any misfortune compare to Mine.

The first passage (part of Christ's speech from the cross in the York Crucifixion play) is Middle English in its original spelling, the second is Middle English but in modern spelling, and the third is 'translated' into modern English.

Early Modern English (EME): from the Tudors (Henry VII was the first Tudor king) to the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, thus encompassing the entire Tudor period, the Elizabethans, Jacobeans, and the period of the Civil War. This is the language of Shakespeare.

If music be the food of love, play on;

Give me excess of it, that surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken and so die.

That strain again, it had a dying fall;

O it came o'er my ear like the sweet sound

That breathes upon a bank of violets,

Stealing and giving odour.

William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night I.I.1-7, edited by Rex Gibson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Modern English (sometimes New English or NE): from the mid-seventeenth century onwards.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice [1813], edited by Vivien Jones (London: Penguin Books, 1996), 5.

Present Day English (PDE) is, like, what we speak now, innit? c u l8r!

Thursday, 17 September 2015

UoA Arts Impact Poster Competition

For the All Blacks, On the Eve of the World Cup

(with apologies to Rudyard Kipling)

If you can catch the ball when all about you

Are dropping it and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when the public doubts you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can win after all the waiting

(Ignore the doomsayers, just deal in tries)

And, though some hate Poms, don’t deal in hating

Just play your best (and hope Hanson’s wise);

If you can think - how to run that bit faster

If you can dream - and make that Cup your aim;

If you can secure triumph, avert disaster

And always play an honest game;

If you can force heart and nerve and sinew,

Scoring tries long after they are gone

And so play on when there is nothing for you

Except the Crowd which roars “Come on!”;

If you can please the crowd and keep your virtue

Or dine with kings - nor lose the common touch;

If neither ‘Boks nor Wallabies can beat you,

If all fans count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of kicking done -

Then yours is the Cup and New Zealand with it,

And - which is All - you’ll be a ‘Black, my son!

If you can catch the ball when all about you

Are dropping it and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when the public doubts you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can win after all the waiting

(Ignore the doomsayers, just deal in tries)

And, though some hate Poms, don’t deal in hating

Just play your best (and hope Hanson’s wise);

If you can think - how to run that bit faster

If you can dream - and make that Cup your aim;

If you can secure triumph, avert disaster

And always play an honest game;

If you can force heart and nerve and sinew,

Scoring tries long after they are gone

And so play on when there is nothing for you

Except the Crowd which roars “Come on!”;

If you can please the crowd and keep your virtue

Or dine with kings - nor lose the common touch;

If neither ‘Boks nor Wallabies can beat you,

If all fans count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of kicking done -

Then yours is the Cup and New Zealand with it,

And - which is All - you’ll be a ‘Black, my son!

Tuesday, 15 September 2015

Films to watch | Shakespeare in Love

| http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/01999/joseph-fiennes_1999093c.jpg |

No, Mr Fiennes, you do not look drop-dead-gorgeous. Just rather thick.

This piece is adapted from work originally submitted as part of the assessment for English 774: Theatre on Screen, Semester 2 2014.

The film is rated M for coarse Elizabethan language (pretty similar to coarse modern language) and for a couple of scenes with a significant lack of clothing.

Laughter, colour and wit are the hallmarks of Shakespeare in Love (1998). The film’s director, John Madden, brings to riotous life Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard’s deservedly renowned screenplay. The script is tight, yet dense, rich and endlessly entertaining; the two hour running time feels much less. Walking rough-shod over the all-too common image of Shakespeare as dry, stuffy and inaccessible, the film delights viewers with its energy and liveliness and leaves them still giggling helplessly long after the closing credits.

The film opens with a young, jobbing Will Shakespeare (Joseph Fiennes) suffering from a bad bout of writer’s block, regretting the loss of his “muse.” No one regrets it more, however, than Philip Henslowe (Geoffrey Rush), who has commissioned Shakespeare to write a crowd-pleasing comedy - Romeo and Ethel the Pirate’s Daughter - for his Rose theatre. Henslowe’s creditors are uncomfortably close; he is relying on the play being a commercial success to keep them off his back. Shakespeare, unmoved by Henslowe’s increasing agitations, indulges in languid idleness and introspection - much to the annoyance of Henslowe (and this reviewer).

Meanwhile a young stagestruck noblewoman, Lady Viola de Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow), hatches a plot to infiltrate the Rose’s acting company. Shakespeare - his words, his poetry, and the man himself - is her idol. She attends an audition at the Rose theatre, disguised rather unconvincingly as a boy: Master Thomas Kent. She takes fright, however, at Will’s intense questioning (the first sign of life he shows), and bolts for home. Will, intrigued, tracks ‘him’ to the de Lesseps mansion, where a party is in full swing. Lady Viola’s parents are negotiating her betrothal to the foppish Lord Wessex (Colin Firth), a match of convenience in which Viola is simply a pawn. Will catches sight of Viola, now correctly attired again, and is promptly and predictably smitten - greatly to the ire of Wessex.

Will casts ‘Thomas Kent’ as Romeo without realising who ‘he’ really is. It is not long, however, before he discovers that ‘Kent’ is in fact the woman with whom he is so besotted. Viola is equally enamoured; from then on, the two spend a fair amount of time in her bed. The awareness that Viola must soon marry Wessex only adds to the urgency of their passion. As they make love, Will’s creative muse is re-awakened: their intense and soon to be thwarted desire results in the unwritten comedy Romeo and Ethel morphing into the great tragedy of Romeo and Juliet.

| http://www.empireonline.com/images/image_index/original/44382.jpg |

Awww... how (sickeningly) sweet...

Viola manages to keep up her alias as Thomas Kent among the other Rose actors rather longer than is credible. But ultimately, inevitably, she is unmasked - much to the horror of all concerned. No one, however, is more horrified than Lord Wessex, whose wedding day turns out to be much more exciting than he had bargained for.

The film has an all-star cast, which (mostly) is superb. Unfortunately, however, the two lead actors do not quite measure up to the high standard set by the rest of the cast. Gwyneth Paltrow is a rather bland and insipid Viola; Joseph Fiennes relies on furrowed brow, exceptionally long eyelashes and a half unbuttoned shirt rather than any great acting talent. The two of them seem at their most animated when in bed, or fervently kissing backstage. Unlike the rest of the characters, their roles hover rather uneasily between the comic and the serious, and the difficulty in negotiating these conflicting demands may account in part for their underwhelming performances. Their comic scenes (such as Viola’s aborted audition) raise a mild titter, but not much more; their more serious moments come across as self-consciously cloying.

The rest of the casting, however, is so strong that it more than makes up for the disappointing performances of Paltrow and Fiennes. The many secondary characters are joyously played for maximum comic effect. Colin Firth, sporting curled forelock, delicate moustache and swinging pearl earring, is glorious as the odious, mercenary fop that is Lord Wessex. His performance here will break the heart of the many Jane Austen lovers for whom he is the one and only Mr. Darcy (perhaps this was why he took the role.) Playing an ageing, crabbed Queen Elizabeth, Judi Dench is superb - but then, she always is. Imelda Staunton, as Viola’s nurse, does what she does best, perfectly portraying a bustling, rustling busy-body who nevertheless has a heart of gold.

| http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-images/Film/Pix/gallery/2001/03/30/shinlove.jpg |

O Mr Darcy, where art thou?

The characters involved in the theatre world are also very well played. They tend to split into two groups - those associated with the Curtain theatre and those belonging to the Rose. Due to the fast pace of the film, it is occasionally hard to keep track of the different factions. But by the time the two companies end up engaging in a fierce melée (“A writer’s quarrel. Quite normal,” according to Will) on the stage of the Rose, amid a snowstorm of feathers, it hardly matters.

As Henslowe, Geoffrey Rush is a stock lovable rogue, his character anticipating that of Barbossa in the Pirates of the Caribbean films. All craggy features, rolling eyes, and curling wig, Rush is a hoot. Ben Affleck and Martin Clunes give solid performances as ‘Ned’ Alleyn and Richard Burbage respectively. Joe Robert’s role as the sadistic youth John Webster is a minor one, but he manages to make it rather uncomfortably convincing. Another minor character, Hugh Fennyman, is milked for all its comic worth by Tom Wilkinson. Simon Callow, as a seedy Master of the Revels, rounds out the cast of colourful core characters.

The film’s greatest strength is that it does not take itself too seriously. Determinedly witty, yet effortlessly lighthearted, it sweeps viewers along in its boundless enthusiasm. Really it is a very silly film in almost every way - certainly in plot and characterisation - but it refuses to pause long enough to allow the viewer to be aware of this. The pace is as fast and urgent as Viola and Will’s star-crossed love affair.

References to Shakespeare’s words and works are peppered throughout the film, ranging from the blatantly obvious (Will and Viola’s ‘balcony scene’) to the much more subtle (Will’s sigh of “words, words, words” when stretched out upon Dr Moth’s couch). The intertextual references, however, are never forced. Apart from the obvious use of the plays and sonnets, much of the word play and the humour arising from this will be picked up only by an alert viewer who knows the Elizabethan theatre scene reasonably well. Examples of this include the rivalry between Shakespeare and Marlowe, author of the hugely popular Dr Faustus. Apart from Viola-as-Kent, all the auditioning hopefuls quote from Marlowe’s play, much to Shakespeare’s fury. John Webster’s sick habit of feeding live mice to stray cats is a reference to the reputation he gained as being one of the most blood-thirsty Jacobean playwrights, producing macabre works such as The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil.

As a whole, the plot of the film also incorporates many elements of Shakespearean drama: ill-fated lovers, disguise and mistaken identity, challenges and duels. The jokes and wordplay add hugely to the humour of the film, yet they are not essential to it. The film can hold its own both with Shakespeare aficionados and Shakespeare ignorami. It challenges the former but does not patronise the latter; the film’s merriness, colour and vibrancy ensures that it can be enjoyed on many levels and by a wide-ranging audience.

The film’s continual blending of the historical with the fictional can be slightly disconcerting, especially for those accustomed to treat Shakespeare with more reverence than the director and writers do. The mix of true historical figures (most of the named actors and playwrights in the film have historical counterparts) with the invented (Lady Viola, Lord Wessex) is mildly confusing but works well within the plot and structure of the film. For the Shakespeare purists, however, there is plenty of nit-picking to be done. Among other howlers, the film’s opening sets the year as 1593, but during most of this year the playhouses were closed due to the plague. In 1593 the Chamberlain’s Men did not exist; the company was not founded until the following year. Marlowe is depicted as a couple of decades or more older than Shakespeare; in reality, they were the same age. The date and location for the first staging of Romeo and Juliet is uncertain, but what is certain is that it was not at the Rose theatre. Virginia, where Lord Wessex supposedly has his tobacco plantations, was not colonised by the British until 1607. And, most glaringly, Shakespeare’s fling with Lady Viola de Lesseps, around which the entire plot turns, is completely imagined.

| http://www.hotflick.net/flicks/1998_Shakespeare_in_Love/big/fhd998SIL_Judi_Dench_006.jpg |

Queen Elizabeth in all her glory

But to focus too much on these historical inaccuracies is to lose the point of the film. It is a self-styled romantic comedy; it does not set out to provide an historical documentation of Shakespeare’s life. Part of the playwright’s fascination (or frustration) for so many people is the fact that we know so very little about his life. People try to fill in the gaps, fleshing out the few scanty details we do have. The makers of Shakespeare in Love are by no means the first to do this and they certainly will not be the last. They are, however, probably unique in that they have managed to do it with an outrageous irreverence that nonetheless comes off.

Some of the anachronisms - Dr. Moth’s psychoanalysis couch, the ugly little souvenir mug marked “A present from Stratford-Upon-Avon” - are so ridiculous that one can only laugh and let them pass. But, these aside, the film actually offers a good sense of sixteenth century London and its theatre. The sets for the Rose and Curtain theatres, in which so much of the critical action takes place, are true to what we know London playhouses of the time to have looked like (even though this is admittedly largely conjecture and guesswork, subjected to much squabbling by eminent historians and Shakespearean scholars). There is a nice (if that is the word) feel for London lowlife, and the predominance of bars, pubs and brothels, along with the implied suggestion that members of the theatrical world spent a fair amount of time drowning their sorrows in such haunts.

The costumes help the atmosphere of the film, too, especially the sumptuous, colourful outfits of the more aristocratic characters such as Lord Wessex and Lady Viola (when she does appear as Viola. Her silly little moustache which she sports as Thomas Kent is peculiarly but unrelentingly irritating). Judi Dench’s Queen Elizabeth attire, however, trumps them all. Scowling, powdered face, receding hairline at the front, masses of heavy red hair piled up at the back, huge skirts and massive peacock-feathered collar - Dench is the uncanny epitome of the ageing Queen.

That moustache. 'Nuff said.

One cannot help but wonder what Shakespeare himself would make of this film. Would he approve? Would he recoil? Of course we can never know. Ultimately, however, it does not really matter. The film embraces human life, with all its idiosyncrasies, fears and joys, ups and downs, frustrations and triumphs. And that is precisely what Shakespeare’s works do. For all its parody, the film stands testimony to the Bard’s enduring power and appeal.

Friday, 11 September 2015

Springtime in Auckland

Spring is sprung,

The grass has ris,

If you want to know where the birdies is...

... they're all up in the blossom trees getting drunk and disorderly on the nectar!

The grass has ris,

If you want to know where the birdies is...

... they're all up in the blossom trees getting drunk and disorderly on the nectar!

Thursday, 10 September 2015

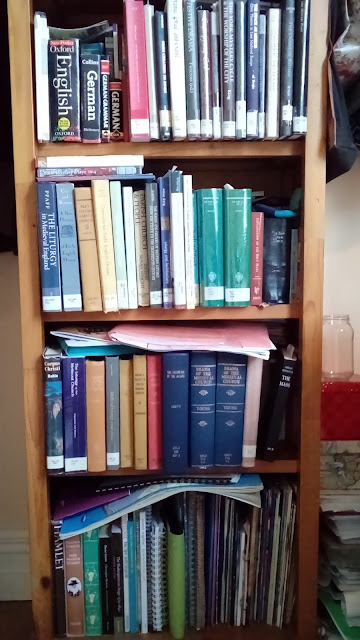

The many bookshelves of an English student

|

| Work bookshelf: |

|

| Thesis books... |

| |

| more thesis books... |

| ||||

| ... and yet more thesis books. The Middle English section of the university library has found a new home :P |

|

|

| Organised (yes really) chaos |

|

| Old friends |

|

| Penguin Classics: the hallmark of English students |

|

| What to do when one runs out of room for more thesis books? Stack them on the floor, of course :) |

Wednesday, 9 September 2015

The Mercers' Pageant Documents

The Mercers are beloved by students of the mystery plays because they kept detailed records - particularly in 1433, when they helpfully produced a list of all the scenery and props used in their play. These records are enormously helpful in working out how their play was staged and what it looked like. By extension, some of the information gleaned from the Mercers' pageant records can be tentatively applied to other plays as well. For example, the Mercers probably used a two-storey wagon, which modern productions (especially the groundbreaking 1998 York/Toronto production, which performed all forty-seven plays in order across a single day) have proved to be feasible and not necessarily dangerously top-heavy as was previously thought. Other guilds, therefore, may well have used these double-decker wagons as well, giving themselves more playing space - a pageant wagon is not very big, so all available space would have been utilised, as well as the area in the street around the wagon.

The Mercers' play was the Doomsday or Last Judgement, which gives lots of scope for show and spectacle. The most famous prop listed in the play records is the hell mouth, which would have been underneath the wagon top, allowing the Bad Souls to tumble symbolically from the playing space down into hell. The red-painted devils could also have come up through the mouth to drag off their victims.

The hell mouth (probably in the shape of a dragon's head and painted in fiery colours) would have been counterbalanced visually by heaven, which appears to have been a kind of canopy or balcony over the wagon floor. At any rate, "iiij Irens to bere vppe heuen" [four iron poles/bars to bear up heaven] are called for. Heaven itself is "of Iren With a naffe of tre ij peces of rede cloudes & sternes of gold langing to heuen ij peces of blu cloudes... iij peces of rede cloudes With sunne bemes of golde" [of iron with a roof (?) of wood (? possibly leafy branches), two pieces of red clouds and stars of gold hanging from heaven, two pieces of blue clouds and three pieces of red clouds with sunbeams of gold].

My favourite prop is the "brandeth of Iren þat god sall sitte vppon when he sall sty vppe to heuen" [a swing of iron that God shall sit upon when he shall ascend up to heaven]. Obviously there was some kind of pulley system that hauled the actor playing God up from the floor of the pageant wagon to heaven up above. Sadly, no one seems to have utilised such a wonderful piece of visual imagery in any modern production.

All that iron must have made the wagon incredibly heavy. How the poor people who had to push the wagon did it we have no way of knowing, as scenery in modern productions is made out of rather more practical materials!

The list of scenery and props is highly detailed, sometimes peculiarly so - the pageant wagon, for example, is listed with the specification that it must have four wheels! (Just in case someone got stingy and decided it would be cheaper to have only three, presumably...)

Among details of various props and costumes are such gems as "A lang small corde" [a long small cord] which was something to do with "þe Aungels" that "renne aboute in þe heuen" [the angels that run about (yes, that is the translation) in heaven]. What the cord (or rope) was actually used for is not specified. As a leash, perhaps, for God to control the angels in case their running about got a little too lively? What a glorious image!

Also listed are "vij grete Aungels halding þe passion of god" [seven great/big angels holding the instruments of the Passion]. This means that the angels would have been holding the Arma Christi to illustrate the speech where Christ calls on the audience to look at the wounds inflicted for their redemption:

Here may ye see my wounds wide,

The which I tholed for your misdeed.

Through heart and head, foot, hand, and hide,

Not for my guilt, but for your need.

Behold both body, back, and side,

How dear I bought your brotherhead.

These bitter pains would I abide -

To you buy you bliss thus would I bleed.

My body was scourged without skill,

As thief full throly was I threat;

On cross they hanged me, on a hill,

Bloody and blo, as I was beat,

With crown of thorn thrusten full ill.

This spear unto my side was set -

Mine heart-blood spared they not for to spill;

Man, for thy love would I not let.

The actor playing Christ wore "a Sirke wounded" - a shirt (probably more like a long robe-like garment) that had been torn or slashed and then spattered with red to represent Christ's wounds.

All quotes from Mercers' Pageant documents [1433] from Records of Early English Drama, edited by Alexandra Johnson and Margaret Rogerson (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1979), 55. Translations in square brackets my own. Christ's speech from the Last Judgment from The York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling, edited by Richard Beadle and Pamela King (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 275-6, l.245-60.

Tuesday, 8 September 2015

Looking back: 2012 York Mystery Play Production

Some links to video clips used to promote the 2012 production. Like the upcoming 2016 run, this was a 'fixed place' production - instead of using the pageant wagons the plays were performed on one large stage. This was erected in the Museum Gardens, using the ruins of St Mary's Abbey as a backdrop.

The clips give a good sense of the colour, movement, and sheer scale of the mystery plays. One theme that comes up again and again is how important the plays are to York's history, community, and the city itself.

All clips from http://www.yorkmysteryplays-2012.com/page/videos_and_podcasts.php

Cinematic trailer

Teaser trailer

The Artistic Directors talk about the staging

Time lapse of the stage & seating going up

Interviews with God/Jesus (Ferdinand Kingsley) and Satan (Graeme Hawley)

The plays and the community

The clips give a good sense of the colour, movement, and sheer scale of the mystery plays. One theme that comes up again and again is how important the plays are to York's history, community, and the city itself.

All clips from http://www.yorkmysteryplays-2012.com/page/videos_and_podcasts.php

Monday, 7 September 2015

One's first academic poster

According to the good old UoA, yours truly is now an 'early career academic.' Ha!

Early career academics (and middle and late career academics, for that matter) are expected to engage in the vague and dubious pastime of "getting one's research out there." To this end I have been having a great deal ofstrife fun lately trying to design a research poster to be entered in the Faculty of Arts Exposure competition. After two weeks of frustration and foot stamping, behold the finished result in all its glory:

Please also note a couple of do's and don't's I wish someone had pointed out to me before I started. (But then, perhaps it's just as well they didn't, or I never would have started.)

DO NOT make the mistake of thinking that designing a poster is a nice, easy, fun little project taking a couple of days at most. Ha!

DO NOT be so foolish as to assume that the colours of your poster when printed will look anything like the colours on your computer screen.

DO be aware that the process involves endless tweaking, fiddling and frustration as well as umpteen trips to the printer... but also a certain amount of satisfaction at the end of it :)

The poster is printed at A1 size but I have a great many spare half-size (A3) mock-ups (see above re umpteen trips to the printer). I never want to see an A3 mock-up again but they are all really quite pretty and would look lovely adorning your wall. If you would like one, let me know. I'll even autograph it for you :)

Early career academics (and middle and late career academics, for that matter) are expected to engage in the vague and dubious pastime of "getting one's research out there." To this end I have been having a great deal of

|

| The quality isn't great because I had to convert it to a PNG file in order to upload it to the blog. To find out how you can acquire your very own higher-quality copy, read on! |

Please also note a couple of do's and don't's I wish someone had pointed out to me before I started. (But then, perhaps it's just as well they didn't, or I never would have started.)

DO NOT make the mistake of thinking that designing a poster is a nice, easy, fun little project taking a couple of days at most. Ha!

DO NOT be so foolish as to assume that the colours of your poster when printed will look anything like the colours on your computer screen.

DO be aware that the process involves endless tweaking, fiddling and frustration as well as umpteen trips to the printer... but also a certain amount of satisfaction at the end of it :)

The poster is printed at A1 size but I have a great many spare half-size (A3) mock-ups (see above re umpteen trips to the printer). I never want to see an A3 mock-up again but they are all really quite pretty and would look lovely adorning your wall. If you would like one, let me know. I'll even autograph it for you :)

Friday, 4 September 2015

2016 staging of York Mystery plays

The York Mystery plays are being wheeled out once again - although for their 2016 staging they will not be performed on the traditional pageant wagons but in the cavernous nave of York Minster. They were first performed here in 2000 to critical acclaim, and next year's production looks set to be just as impressive.

For general info, details, lots of pretty pictures, and even (for English residents!) the chance to get involved, see the production's spanking new website: Mystery plays 2016

Moving the plays inside the church will make for some interesting dynamics, as they were never intended to be staged indoors. The 'stations' or stopping points on the original pageant route were all either in front of or very close to churches (they made handy landmarks), but the plays belonged very much to the streets and their urban setting.

The plays as originally staged can be thought of as turning the churches 'inside out' - turning the action, immediacy and emotional power of the Mass and liturgy into a more accessible form, moving the sacred from the bounds of the church into the secular world of the city. Now we are going the other way - the plays are moving into the church.

For general info, details, lots of pretty pictures, and even (for English residents!) the chance to get involved, see the production's spanking new website: Mystery plays 2016

Moving the plays inside the church will make for some interesting dynamics, as they were never intended to be staged indoors. The 'stations' or stopping points on the original pageant route were all either in front of or very close to churches (they made handy landmarks), but the plays belonged very much to the streets and their urban setting.

The plays as originally staged can be thought of as turning the churches 'inside out' - turning the action, immediacy and emotional power of the Mass and liturgy into a more accessible form, moving the sacred from the bounds of the church into the secular world of the city. Now we are going the other way - the plays are moving into the church.

|

| A ready-made theatre? The vast nave of York Minster |

| ||

| Holy Trinity Church, the first stop on the pageant route |

|

| And the famous octagonal tower of All Saints Pavement, right in the centre of the city, where the pageant route ended. |

| http://eng.1september.ru/2008/08/img10-1.jpg |

Artist's impression of how the mystery plays might have looked as originally staged (this is the Trial of Christ play).

Ego sum Alpha et O: vita, via, veritas, primus et novissimus.

I am gracious and great, God without beginning,

I am maker unmade, all might is in me;

I am life, and way unto wealth-winning,

I am foremost and first, as I bid shall it be.

My blessing of blee shall be blending,

And hielding, from harm to be hiding,

My body in bliss ay abiding,

Unending, without any ending.

This is the beginning of God the Father's speech which opens the first play, The Fall of the Angels, and thus the whole play cycle.

The Fall of the Angels l.1-9, from York Mystery Plays: a Selection in Modern Spelling, ed. Richard Beadle and Pamela King (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Tuesday, 1 September 2015

Feste's Song

When that I was and-a little tiny boy,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

A foolish thing was but a toy,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came to man's estate,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

'Gainst knaves and thieves men shut their gate,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came, alas, to wive,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

By swaggering could I never thrive,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came unto my beds,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

With tosspots still 'had drunken heads,

For the rain it raineth every day.

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

But that's all one, our play is done,

And we'll strive to please you every day.

Twelfth Night V.1.366-85 (Cambridge School Shakespeare edition, ed. Rex Gibson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.)

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

A foolish thing was but a toy,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came to man's estate,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

'Gainst knaves and thieves men shut their gate,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came, alas, to wive,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

By swaggering could I never thrive,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came unto my beds,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

With tosspots still 'had drunken heads,

For the rain it raineth every day.

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

But that's all one, our play is done,

And we'll strive to please you every day.

Twelfth Night V.1.366-85 (Cambridge School Shakespeare edition, ed. Rex Gibson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.)

|

| A wet walk along York's city walls. In England, as everyone knows, it is either raining or just about to. One might say the same thing about an Auckland spring ;) |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)