This piece is adapted from work submitted as part of the assessment for English 783: Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Semester 2, 2014. It represents my contribution to a group assignment whose brief was to write the encyclopedia entry for The Theatre in the Map of Early Modern London (MoEML) Agas Map project (http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/index.htm). The entry is currently being edited and revised for publication. In June Radio New Zealand ran a brief story on the mapping project, which you can listen to here.

As Elizabethan England’s first purpose-built playhouse, the Theatre could take that name without fear of confusion with other London playhouses - which were always referred to in common speech as ‘playhouses,’ not as ‘theatres.’ To Elizabethans the word ‘theatre’ had a wider and richer connotation than has come down to us today. The owner and builder of the Theatre, James Burbage, must have been aware of this. The decision to name his building the Theatre was bold, perhaps even provocative.

Origin and Etymology

The word theatre comes into English from the Latin theātrum. The Latin word comes in turn from the Greek θέᾱτρον, meaning “a place for viewing.” The Greek noun is related to the verb θεᾶσθαι, “to behold,” and also to θέα “sight, view” and θεατής “spectator.” The English word theatre has been in the lexicon since the Middle Ages (first recorded use c. 1374 in Chaucer’s translation of De Consolatione Philosophiae). It retains the sense of looking, viewing, and spectatorship, although in current usage its meaning is restricted to the performing arts and the physical buildings in which they are performed. At the time the Theatre was constructed, the Latin theātrum was used to mean not only a physical space and the action performed in that space, but also much more generally, indicating something worthy of display and to be looked at.

Roman Theatres in Britain

Origin and Etymology

The word theatre comes into English from the Latin theātrum. The Latin word comes in turn from the Greek θέᾱτρον, meaning “a place for viewing.” The Greek noun is related to the verb θεᾶσθαι, “to behold,” and also to θέα “sight, view” and θεατής “spectator.” The English word theatre has been in the lexicon since the Middle Ages (first recorded use c. 1374 in Chaucer’s translation of De Consolatione Philosophiae). It retains the sense of looking, viewing, and spectatorship, although in current usage its meaning is restricted to the performing arts and the physical buildings in which they are performed. At the time the Theatre was constructed, the Latin theātrum was used to mean not only a physical space and the action performed in that space, but also much more generally, indicating something worthy of display and to be looked at.

Roman Theatres in Britain

Though it was the first permanent Elizabethan theatre, the Theatre was not the first to be built in England. The ruins of twenty Roman amphitheatres have been found scattered throughout Britain by modern archeologists, including one at London. The amphitheatres were used “to stage spectacle:” gladiator fights, beast fights, and criminal executions. Of particular interest is the Roman theatre at Verulamium (now St Albans). It is the only known example of a Roman theatre in Britain with a thrust stage rather than an arena. This indicates that theatrical performances were staged there, although the building could still have been used for fights (both animal and gladiatorial) as well.

An artist’s impression of the Verulamium theatre, based on the excavated groundplan, is strikingly similar to conjectural reconstructions of Elizabethan playhouses. Similarly, we know that several London playhouses also served two functions, being used both for theatrical performances and for bear bating. There is no evidence, however, that the Theatre had such a dual purpose.

By the end of the fourth century AD the Verulamium theatre was no longer in use as a venue for the performing arts (it actually became the town’s rubbish site). The amphitheatres also fell into ruin after the Roman withdrawal from Britain. There is no evidence, or records of any kind, for any amphitheatres surviving to the Elizabethan period. We thus have no way of knowing whether Burbage and his contemporaries would have been aware of their former existence. However, the Elizabethans were devoted to the Greek and Roman classics. Even if they were not aware that Britain had had its own amphitheatres, knowledge of the Roman theatres, their appearance and function probably survived.

| Artist's impression of the Verulamium theatre, via |

The Classical Tradition

Burbage may have wished to evoke the classical Roman tradition of theatre, both in the Theatre’s almost circular shape (clearly comparable to the Roman amphitheatres) and in its name. As Andrew Gurr has put it: “His choice of a Roman name and the circular design suggests that he may have had grandiose ambitions to provide London with a copy of one of Rome’s great inventions. Its name affirms that it was not just another converted innyard” (The Shakespearian Playing Companies 189). But if Burbage hoped that this would lend an aura of respectability to his theatre and the performance of plays in it, he was to be disappointed. The Puritans, following the wake of early church fathers such as Tertullian and Augustine, continued to condemn the practice of theatre going and performance as occasions of gambling, drunkenness, prostitution and general moral degradation.

Theatrum Mundi: books

The word theātrum is of course closely associated with the phrase theātrum mundi (theatre of the world), a concept which is especially associated with the Renaissance and the Baroque style. The concept is most familiar to us today as Shakespeare expresses it in As You Like It:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts... (As You Like It, 3.1.139)

But the concept of theātrum mundi was by no means limited to the stage and a literal theatre. Several book roughly contemporary with the Theatre contain the word theātrum in their titles:

Theatrum Vitae Humanum c. 1565 (an early encyclopedia)

A Theatre for Worldlings 1569 (religious treatise)

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum 1570 (considered to be the first modern atlas)

Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum mulierum 1586 (encyclopedia of women’s national dress)

Theatrum de veneficis 1586 (treatise on black magic)

Theatrum Mundi, et Temporis 1588 (maps of star constellations)

Theatrum artis scribendi 1594 (treatise on handwriting)

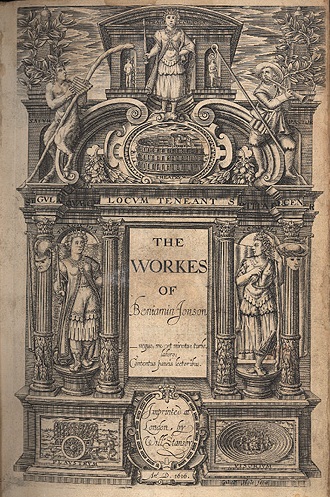

The frontispieces of these and other Elizabethan books are highly detailed and richly symbolic. Several include representations of the physical world, many contain some reference to the theatre (such as, famously, Benjamin Jonson’s 1616 folio frontispiece image) and almost all incorporate a physical structure of some kind - usually a stone arch or monument. This last is important, because the purpose of frontispieces was not merely to provide decoration. Instead they were designed to “epitomise the book and glorify its author and his work” (Corbett and Lightbrown, The Comely Frontispiece 46). Burbage may have intended the Theatre to be his monument, a physical testimony to his life and work, more impressive and imposing than a mere page in a book.

|

| Frontispiece to 1616 Jonson portfolio, via |

Theatrum Mundi: Kunstkammern and ‘Cabinets of Curiosities’

Throughout the sixteenth century the royal Habsburgs compiled miscellaneous objects of value or beauty - jewellry, artifacts, curiosities, relics, paintings, objects from the natural world, carvings and sculptures - and housed them in collections known as Kunstkammern. One of the most important of these collections was that of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol (1529-1595), whose Kunst- und Wunderkammer [chamber of art and natural wonders] was “a reflection of the cosmos and thus of contemporary knowledge about the world” (Haag, “A History of the Kunstkammer Wien”). Kunstkammern and similar collections were described by Samuel Quiccheberg in his 1565 Inscriptiones vel tituli theatri amplissimi as theātri mundi, “theatre[s] conceived in the broadest possible terms, containing genuine materials and accurate reproductions of the whole universe”(Friehs, “Art and Junk”).

Kunnstkammern first appeared in England as ‘cabinets of curiosities’ around the turn of the sixteenth century - slightly later than their European counterparts. The earliest significant English collection is the Tradescant collection, first referred to in 1634. By this time the collection was already “encyclopaedic,” so Tradescant must have been collecting for some time. Consequently, even though the first record of the collection comes considerably later than the construction of the Theatre, it seems not unreasonable to assume that the idea of Kunnstkammern as theātri mundi filtered back to England much earlier. Burbage may well have had this in mind when naming the Theatre.

|

| Cabinet of Curiosities, via |

Show and Spectacle

So in the Renaissance period the idea of a theātrum, or theatre, extended far beyond a physical space. The underlying concept of a theātrum was to present and showcase the universe in manageable form for study and spectatorship. Whether in the pages of a book or in a Kunnstkammer, the aim was to present “in a small space... an all embracing image of the world” (Haag, “A History of the Kunstkammer Wien”). We still think of the theatre as doing this: for many, one of the purposes of the theatre is how life is reflected in art. For the Elizabethan playgoers, the image of heaven, earth and the cosmos was incorporated into the physical structure of the theatre building. We know that the underside of the tiring-house roof in several of the playhouses was painted to represent the heavens, including depictions of the sun, moon, stars and the signs of the zodiac. The stage represented earth and the hollow area beneath it hell. Thus the whole cosmos was represented in the physical structure of the stage. There is unfortunately no surviving evidence of how the Theatre’s stage looked, but also no reason to assume that it varied greatly from this basic model.

Conclusion

In naming the Theatre, Burbage assigned his playhouse a markedly different status from that of the inn-yards previously used for performances. By evoking the ancient Roman theatres, he claimed for it dignity and prestige. The name also links into contemporary notions of theatre, show and spectacle.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: WORKS CITED OR CONSULTED

Allen, Mia. The Tradescants: Their Plants, Gardens and Museum, 1570 - 1662. London: M. Joseph, 1964.

Corbett, Margery, and Ronald Lightbrown. The Comely Frontispiece: The Emblematic Title Page in England, 1550 - 1660. London; Boston: Routledge and Paul, 1979.

Friehs, Julia Teresa. “Art and Junk: The Habsburgs and Their Cabinets of Art and Curiosities.” The World of the Habsburgs. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.habsburger.net/en/stories/art-and-junk-habsburgs-and-their-cabinets-art-and-curiosities

“Frontispiece.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/view/Entry/74941? rskey=ZX5RJQ&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearian Playing Companies. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

------- The Shakespearean Stage 1574 - 1642. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Haag, Sabine. “A History of the Kunstkammer Wien.” Kunst Historisches Museum Wien. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.kkhm.at/fileadmin/content/KHM/kkhm/Presse/ History_of_the_Kunstkammer.pdf

Kenyon, Kathleen. “The Roman Theatre of Verulamium: Reprinted From the St Albans and Hertfordshire Architectural and Archeological Society’s Transactions, 1934.” Accessed September 10, 2014. http://www.infotextmanuscripts.org/webb/webb_roman_t.pdf

Stern, Tiffany. “‘This Wide and Universal Theatre’: The Theatre As Prop in Shakespeare’s Metadrama.” In Shakespeare’s Theatres and the Effects of Performance, edited by Farah Karim-Cooper and Tiffany Stern, 11-32. London: Arden Shakespeare, 2013.

“Theatre.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/view/Entry/200227?rskey=2gyziM&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

“The Tradescant Collection.” Ashmolean Museum. Accessed August 19, 2014. http://www.ashmolean.org/ash/amulets/tradescant/tradescant03.html

The Roman Theatre of Verulamium. Accessed September 10, 2014. http://www.romantheatre.co.uk

Wilmot, Tony. “Roman Amphitheatres, Theatres and Circuses.” English Heritage. Accessed September 10, 2014. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-roman-amphitheatres-theatres-circuses/amphitheatres.pdf

Allen, Mia. The Tradescants: Their Plants, Gardens and Museum, 1570 - 1662. London: M. Joseph, 1964.

Corbett, Margery, and Ronald Lightbrown. The Comely Frontispiece: The Emblematic Title Page in England, 1550 - 1660. London; Boston: Routledge and Paul, 1979.

Friehs, Julia Teresa. “Art and Junk: The Habsburgs and Their Cabinets of Art and Curiosities.” The World of the Habsburgs. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.habsburger.net/en/stories/art-and-junk-habsburgs-and-their-cabinets-art-and-curiosities

“Frontispiece.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/view/Entry/74941? rskey=ZX5RJQ&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearian Playing Companies. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

------- The Shakespearean Stage 1574 - 1642. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Haag, Sabine. “A History of the Kunstkammer Wien.” Kunst Historisches Museum Wien. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.kkhm.at/fileadmin/content/KHM/kkhm/Presse/ History_of_the_Kunstkammer.pdf

Kenyon, Kathleen. “The Roman Theatre of Verulamium: Reprinted From the St Albans and Hertfordshire Architectural and Archeological Society’s Transactions, 1934.” Accessed September 10, 2014. http://www.infotextmanuscripts.org/webb/webb_roman_t.pdf

Stern, Tiffany. “‘This Wide and Universal Theatre’: The Theatre As Prop in Shakespeare’s Metadrama.” In Shakespeare’s Theatres and the Effects of Performance, edited by Farah Karim-Cooper and Tiffany Stern, 11-32. London: Arden Shakespeare, 2013.

“Theatre.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed August 18, 2014. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/view/Entry/200227?rskey=2gyziM&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

“The Tradescant Collection.” Ashmolean Museum. Accessed August 19, 2014. http://www.ashmolean.org/ash/amulets/tradescant/tradescant03.html

The Roman Theatre of Verulamium. Accessed September 10, 2014. http://www.romantheatre.co.uk

Wilmot, Tony. “Roman Amphitheatres, Theatres and Circuses.” English Heritage. Accessed September 10, 2014. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-roman-amphitheatres-theatres-circuses/amphitheatres.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment